Thanks for joining me! This email contains the second chapter from my “Dreaming In the Real” manuscript, a work in progress. Bi-weekly episodes reveal how immersing myself in the natural world while preparing vibrational essences helped me gain insight and healing after my adult life crumbled due to unaddressed trauma and childhood adversity.

PLEASE START HERE to access the episode list and preceding chapters. A book is best read chronologically.

CONTENT GUIDANCE: This manuscript tackles sensitive themes of parental neglect, abuse, drugs, and domestic violence. Reader discretion is advised.

“Children don’t get traumatized because they are hurt. They get traumatized because they’re alone with the hurt.” ~ Dr. Gabor Mate, The Wisdom of Trauma

AS WITH MOST PERSONAL history, mine started before I came into the world. I wasn’t there, but I feel like I was. My parents, Katherine and Orville, were married for twenty-two years and in their mid-forties when I was born, each bringing the dysfunction of unaddressed trauma to their relationship. Most of their history is disputed among family members since we all hear inconsistent stories from different people, and memories are frequently unreliable.

Orville, the second youngest of six children, was born in 1916 into a close-knit Norwegian Protestant family. A black-and-white photo captures a moment of pure joy, with Orville and his siblings sitting on a fence in front of the family barn in Colton, South Dakota. Dressed in a white button-down shirt, knickers with suspenders, and a beaming smile, the photo exudes a warmth I rarely saw. Despite the hardships of the Great Depression, he graduated from twelfth grade in a one-room schoolhouse with the highest marks.

After he graduated, he hitchhiked to California, hoping to build a better life by picking fruit alongside migrant workers and farmers who fled the Dust Bowl states. Even with the discipline and frugality of a Scandinavian work ethic, I’m still amazed that he saved enough money to purchase a full-service gas station in Sacramento.

Katherine was born in 1918 into a mixed English, Scottish, and Irish Catholic family in Fullerton, California, on the day the First World War ended. A childhood photo shows her on one of her father’s imposing Clydesdale horses, sitting tall with her thick, dark hair cropped short. Even though she wasn’t smiling, I like to think that as tiny as she was, she held the reins and imagined she ruled the world.

When she was barely twelve, Katherine’s mother fled to England to escape her husband’s alcohol-induced abuse. Katherine never saw her again. Her youngest brother went to live with an uncle, and she stayed with her father and oldest brother, running away from home several times before her father placed her in a disciplinary boarding school. After running away from the boarding school, no one knew where she went, what she did, or how she survived the worst economic downturn in US history.

The Great Depression was ending when a recently widowed, twenty-one-year-old Katherine returned home with a baby boy named Paul. Her father, already dealing with a new wife and baby of his own, wasn't thrilled to have his wayward daughter back. He presented her with two options: work as a housekeeper for a wealthy family he knew or get married.

Orville's service station sat across the street from Katherine's father's workplace, and the two men had formed a friendship over a weekly poker game. Orville and Katherine met and married in the fall of 1939. Both were young, beautiful, and intelligent, but I imagine it was more a marriage of convenience than love. For Katherine, it was a way to survive.

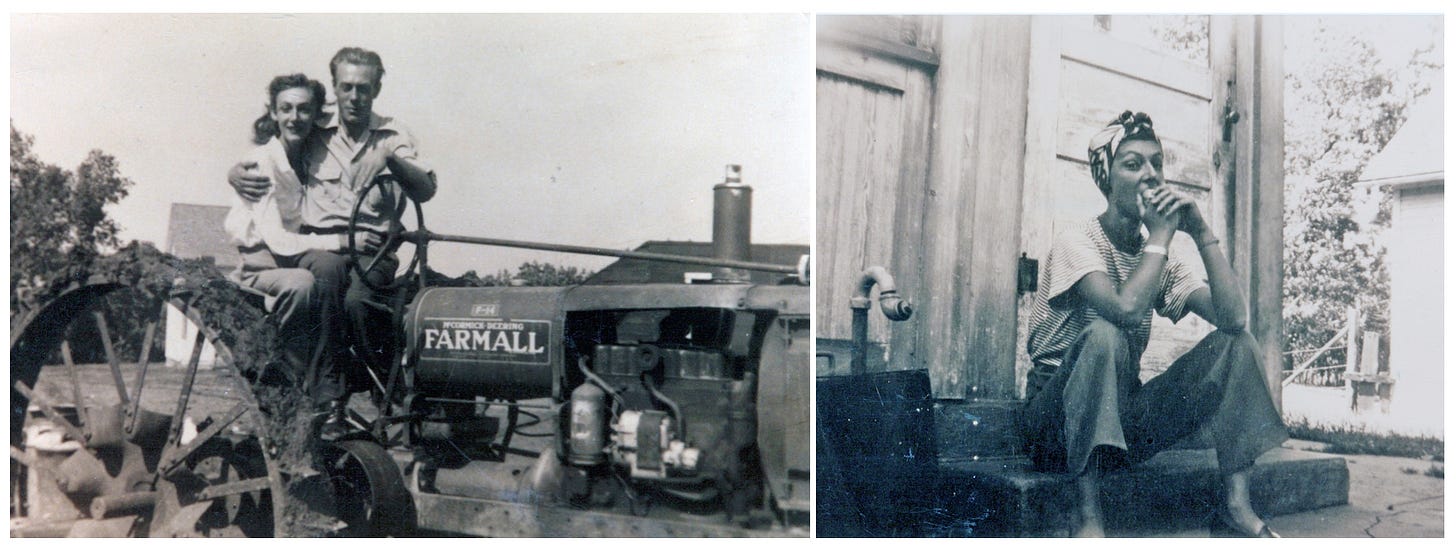

In the spring of 1941, Katherine gave birth to a baby girl, who I will refer to as Nancy. A few years later, Orville was conscripted into the Army and served in the Allied occupation of Germany during World War II. When he returned, he moved his family to a farm in South Dakota.

I’ll always remember this story my mom told me about life on the farm.

With no indoor plumbing, she carried water in a bucket from the outside hand pump to heat inside on the electric stove. With her long hair tied back with a scarf and rubber gloves protecting her hands from the hot water and ammonia, she worked on her hands and knees, stripping off old, yellowed wax from the farmhouse's linoleum floor before carefully applying a new wax finish. By the end of the day, her body ached.

Hearing my dad return after working in the fields, she yelled from a window to wait because the wax on the floor was still wet. He heard her but walked in anyway, purposely destroying her hard work by stomping back and forth throughout the house in his muddy field boots.

“Don’t ever tell me what to do,” he raged.

Paul lied about his age in a desperate attempt to break free from his stepfather's bullying and joined the Navy at seventeen. Nancy's story, too, was filled with hardships. She became pregnant at sixteen, leading to an elopement, a divorce, and a second marriage. By the time she was twenty, she was expecting her third child.

Orville soon sold the farm and accepted a position with the USDA. He and my mom relocated to the outskirts of Madison, a small town in the southeast corner of the state, where his youngest sister lived.

MY MOM WAS UNCONSCIOUS when I was born in March of 1961. With all the risks of a late-life pregnancy, she was under anesthesia during a forceps-assisted delivery. Nurses provided the first five days of my care while she recovered in the hospital. Like many children of the late fifties and early sixties, my nourishment came from formula made with fortified evaporated cow’s milk.

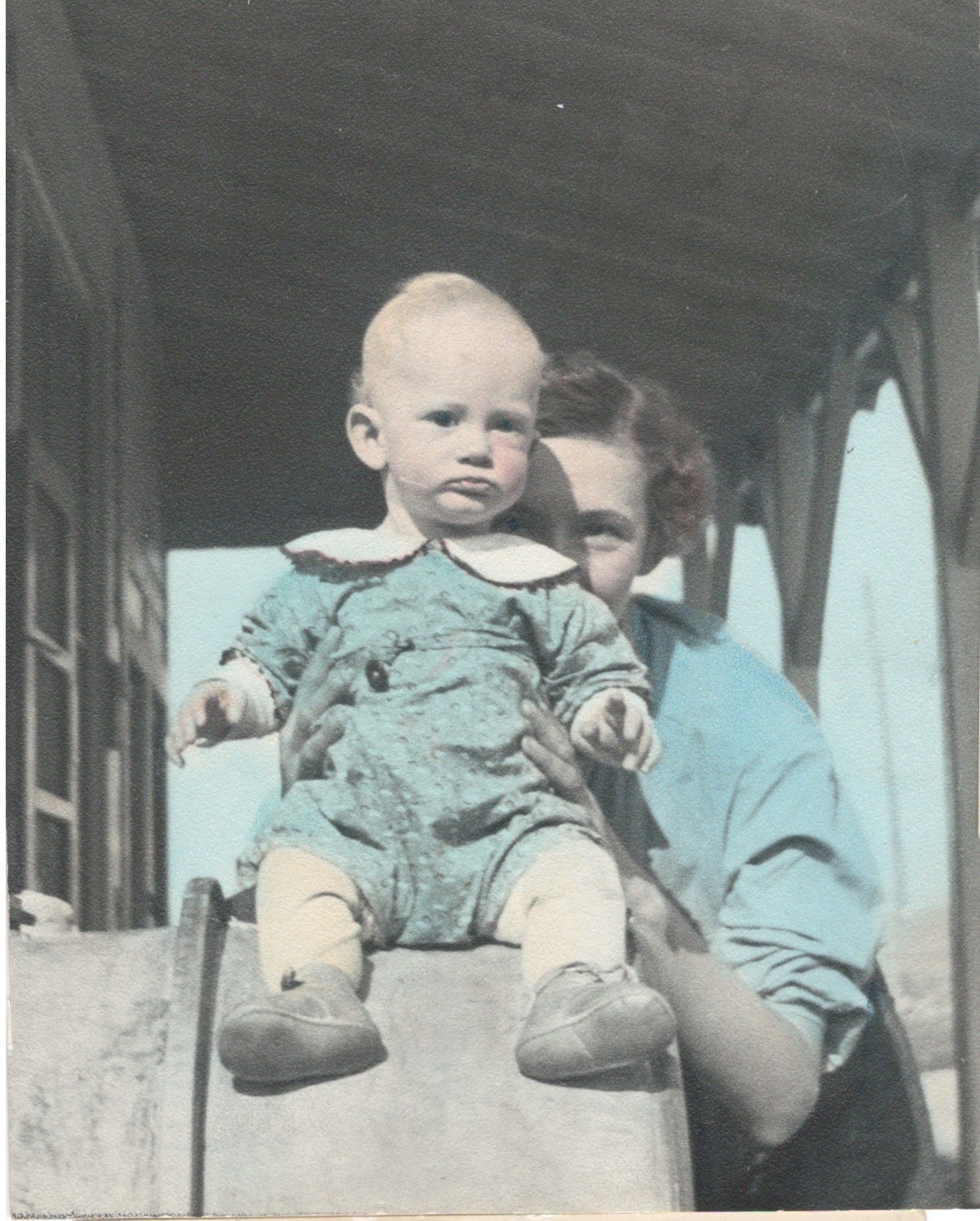

Before I turned one year old, my mom made her own attempt to leave my dad. She took me to stay with Nancy and her family on their farm outside Sioux Falls. When my mom refused to come home, my dad told our family doctor to have her involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. Fortunately, in the era of “doctor knows best,” our wise family doctor refused.

Desperate, Orville threatened, “If you don’t come back, I’ll take Marnie away, and you will never see her again.”

Feeling powerless to do anything else, she went back.

I DON’T REMEMBER my dad ever touching me beyond the occasional spankings when he was angry about something else. I have black and white photos of him holding me when I was really little, but the only time I remember him holding me was when I pretended to be asleep in the backseat of the car at the end of long journeys, and he carried me into the house.

When I was little, my dad and I played checkers and rummy. He even took me fishing once. We dug for worms, and he showed me how to put them on the hook, set the bobber, and patiently hold my bamboo pole at the lake's edge. I felt excited as I pulled in a small perch and was proud when my mom cooked it for my dinner. For some reason, we never went fishing again. I vaguely remember moments when he was warm and funny, but they were always cut short by what seemed like a pervasive discontent.

Recurring nightmares disrupted my childhood sleep. A menacing dark cloud would twist into shapes of monstrous wounded animals and follow me as I ran up wooden stairs and down hallways, seeking refuge in closets, afraid for my life. The dark cloud seeped under locked doors, leaving me with no escape. Waking with a pounding heart, I'd turn on my bedside lamp and pull the covers over my head. During the day, I avoided my dad, just like I did the dark cloud. I stayed quiet and went to my room whenever he came home. I hoped that by staying out of the way, he wouldn't see me, I wouldn't upset him, and he wouldn't be cruel to my mom.

He held the power in our family, so I think in those years, the bulk of my mom's influence was limited to me. Lacking her own personal agency, she didn't allow or encourage me to have any. For instance, when we went to the lake and my cousins played in the water, even those younger than me, I wasn't allowed to get in past my ankles.

Whenever I asked why, she’d say, "Because you can't."

I internalized the invalidation, believing I was incapable of the simple and normal activities that other kids effortlessly mastered.

Despite the dysfunction, my mom was my person. We snuggled together and snacked on buttered popcorn while watching The Magical World of Disney and Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom. She taught me how to set a formal table and invited a neighbor to show me how to host a proper English tea. Using brightly colored fabrics from the '60s, she sewed us matching outfits. When she took art and oil painting courses at the local college, she, in turn, encouraged my creativity. She rarely let me use coloring books; instead, she had me draw my own pictures to color. She set me up with projects like painting small macaroni with bright watercolors and stringing colorful necklaces. She taught me how to make paper chains and weave paper baskets and Chinese lanterns using multicolored paper, safety scissors, and paste.

WHEN I WAS four or five, my parents hosted a Fourth of July picnic. Our yard held several plywood tables covered with colorful linen tablecloths, heaping bowls of macaroni salad, and platters of cold fried chicken. I didn’t know I had so many cousins. The youngest of us set off mini firecrackers, ignited winding black snakes and colorful smoke bombs, and created designs in the air with fiery sparklers. My older cousins blew up tin cans with real firecrackers and prepared the fireworks for the evening display on the low-lying hill behind the house. I was sure heaven had descended onto our little acreage.

With what seemed like a bird’s-eye view from the top bar of my swing set, I saw a handsome stranger hugging my aunts and uncles and joking with my older cousins. Even with a short flattop haircut, he stood inches taller than everyone else. When he found me, I was on the ground watching a black smoking snake uncoil across the sidewalk. Sinking to one knee, he looked into my eyes.

“Hi, Marnie. I’m your brother Paul. It’s my birthday today,” he said.

Then he hugged me so tightly and gently that I didn’t want him to let go.

I was thrilled! I didn’t know I had a brother. I can’t recall how long Paul stayed with us, but he greeted me each morning with a big smile and long arms that swung me high and held me close. We crawled on hands and knees, stalking baby rabbits in a burrow below a fallen tree. We even made a butterfly net from a forked branch and a netted potato bag and chased tiny blue butterflies in the tall grass. We named the blue inchworms who measured their way across stumps and fallen trees. At night, he sat beside my bed, told me stories, and left pennies, dimes, and nickels under my pillow. Sometimes, my bed creaked and moved rhythmically, but I didn’t know why. It’s just a sensory memory. The important thing was I wasn’t alone anymore.

One day, after I'd grown to count on his presence in my life, Paul left without saying goodbye. I never saw him again. My parents didn't tell me why, even after I was an adult, and asked multiple times.

Not long after Paul's departure, I woke to a warm wetness in my bed. The first night was a terrifying experience. I had never wet the bed before. I crept into my parent's room in the dark of night, hoping for comfort from my mom. Instead, frustrated and silent, she furiously scrubbed the damp spot on the mattress and covered it with a towel before adding clean sheets.

My dad's brooding taciturnity and my mom's fearful and quiet submission made me careful not to worsen the situation. From then on, I slept in the wetness until morning. One day, my dad brought home a new twin-sized mattress and a waterproof mattress pad. As I yearned for acceptance and understanding, my mom silently changed my sheets, as if never speaking about it would mean it never happened. So, it became a shameful family secret—something was wrong with me.

Years later, Nancy told me that my dad made Paul leave because he was hurting me. I told her I didn’t remember him ever hurting me, and she became somber, her mouth cutting a tight, straight line across her face. She told me that when Paul was a teenager, he and his friends sexually molested her. I didn’t want to believe her, but her expression dared me not to. I didn’t trust Nancy. She thrived on drama. Still, over the course of digging through my past and confiding in my therapist, I realized that even though I have no memories of it, Paul may have been sexually molesting me. I like to think he was wrongly accused. I don’t know how this affected my adult self, but I did learn how to keep shameful things secret.

Today, I hold that little girl close and tell her, "It's alright. You are perfect, just as you are. Everyone wets the bed sometimes. It's nothing to be ashamed of."

MORE THAN A YEAR after Paul left, my dad survived a widow-maker heart attack. Since kids weren’t allowed to visit inside the hospital, after he’d been there for a week, my mom brought a step stool for me to stand on outside his hospital window. Wanting to cheer him up by showing him I finally learned how to whistle, I knocked on the glass.

My heart sank when he waved me away.

Our family doctor told my dad that he needed to eliminate stress. The doctor also mentioned that even if he did, with the damage to his heart, he would be lucky to live two more years. Because the Dakotas had recently endured one of the deadliest blizzards of the century, and summers bore increasing heat and the destruction of tornadoes, our doctor suggested my dad move us to California. There, the seasons were mild, and my mom would have her family for support when she needed it.

MY PARENTS and Nancy held a moving sale in Sioux Falls. As they worked, I played with my niece and two nephews in the big old Victorian-style home my sister and her husband rented after selling their farm. Almost three years older than me, my niece dominated the rest of us with the kind of teasing that wasn't funny, the kind that elicits control.

My nephews and I laughed and chanted, “Na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, Batman!” running up the stairs to slide down a winding wooden banister, when my niece taunted, “What’s it like having a brother with only one arm? He must look awfully stupid, but he’s dead anyway.”

For a moment, I thought I was falling down the stairs with no one to catch me. But I wasn’t. My nephews were standing beside me, laughing nervously and fidgeting with the bath towels tied around their necks like superhero capes. I ran to my mom, who was busy pricing items for the sale. As usual, she didn’t want to talk about Paul.

As a young adult, I asked my mom again what had happened to Paul, but she remained silent. Turning a blind eye and deaf ear, she passed the pain of being unacknowledged down the line.

Years later, after Nancy deemed me her confidant in everything related to our family dysfunction, she told me about her conversation with the sheriff. My memory of her story is that he took a bullet, and his body was laid across railroad tracks with a shotgun to make it look like a hunting accident, and a train amputated his arm. A historian I later spoke with at the Lake County Museum in Madison speculated his death might have been Klan-related because vigilante Klan activity was still occurring then. But my sister was sure an angry husband killed him for having an affair with his wife.

I often find myself wondering how I can miss someone I barely knew, but I do. Unfortunately, my recent attempts to find Paul's birth and death certificates have failed. I don't know his last name because my dad didn't adopt him, and even if my parents were still alive, they wouldn't tell me anyway. To this day, I have no clue what happened to my almost-brother. But I am determined to find out, to honor and acknowledge his life, and to heal another hidden part of our family's wounds.

NEXT: Chapter 3: A Mother’s Unraveling

Your comments really make my day! I write to connect with people, and hearing what you have to say inspires me to share more. If you can't comment right now, no worries—just drop your thoughts when you can!

You wrote earlier that writing is connection (at least that's how I interpreted it)... and I totally agree with that! Your vulnerability in sharing your childhood experiences feel, to my heart, like a sense of closeness and resonance that I truly appreciate Marnie. Thank you!

Thank you Marnie. This is bravely written stuff!